I've excerpted the article below:

America's DIY ballistics king Bill Gurstelle shoots from the hip about health and safety

Tom Leonard meets the DIY artillery king at his 'barrage garage'.

Bill Gurstelle rams a chunk of russet-brown potato down the business end of a 4ft-long piece of PVC plumbing pipe. He sprays a short burst of hairspray into the other end, screws a cover on and readies his finger on the trigger of an electric stun gun screwed to the piping.

"Could you stand over there, this is kind of dangerous," he says. He's not wrong. Two seconds later, there is a loud bang as the spud explodes out of the pipe at 90mph, taking a branch off a tree 100 yards away.

At that moment, a young woman walks past his backyard in suburban Minneapolis pushing a baby in a buggy. She and Gurstelle smile sheepishly at each other. "They're used to me round here," he says with a shrug. "It's the people who live farther away who tend to call the fire department."

He marches back into his workshop, the "barrage garage", to find something else to detonate. We've already done the fire piston, the carbide cannon and the hot-dog launcher. Soon it will be dark enough to get out his pièce de résistance, a propane flame thrower that sends a jet of fire 30ft into the air.

Gurstelle has been crowned the "king of sling", America's patron saint of DIY artillery. A former telecommunications engineer, he decided to put his mechanical know-how to more practical use and, in 2001, wrote a chatty little book called Backyard Ballistics. Its subtitle, Build Potato Cannons, Paper Match Rockets, Cincinnati Fire Kites, Tennis Ball Mortars and More Dynamite Devices said it all. The how-to-build-with-everyday-items guide went on to become a bestseller – more than 250,000 copies have been sold and it's still going strong.

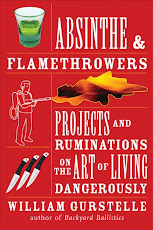

Its 53-year-old author went on to present television shows and catapult out a string of similarly themed sequels. His latest book, Absinthe & Flamethrowers: Projects and Ruminations on the Art of Living Dangerously, is a more contemplative work.

"I wanted to understand why people were reading my books and, secondly, whether it was inherently good for them," he explains. "And I say it is good because it adds a bit of reasonable risk to their lives."

Citing various studies, Gurstelle argues that moderate risk taking has various benefits. Canadian researchers found that managers who took risks were more successful while a German study discovered that people who took more risks said they were happier.

Gurstelle believes his books tap into two rich seams in modern society – contempt for the health and safety bullies, and a more general fear of technology. While he describes himself as a liberal and doesn't own a gun, he's with the libertarians on the issue of being allowed to make your own mistakes.

"We live in the age of the lily-livered, where people make terrific efforts to remove all possible risks from their lives," he says.

"It becomes a fairly pallid, sterile experience. You certainly won't be hurt but you won't be creative. And it's especially true for children. Are they going to grow up to be so risk averse that they don't contribute anything?"

To suggestions that litigious America is bad in this respect, he ripostes that Britain is worse, quoting stories about children wearing hard hats for fossil trips and councils cutting down trees in case conkers fall on people.

Readers also buy his book because they feel overwhelmed by technology, he says. "This DIY movement is about people getting control of the technology in their lives. They want to design and make things, even simple things, rather than just blindly using them."

Not surprisingly, many of his readers are fathers wanting to build his designs with their children (Gurstelle did, though his two sons are now grown-up). A lot are teenagers who, he observes drily, "always like blowing stuff up". Would-be terrorists are not likely readers, he says. There is nothing in his books that is sufficiently lethal.

Gurstelle traces his own path to garage warriordom to a day at university when a friend created a mortar out of empty shaving cream cans and shot a tennis ball over their 10-storey building. "It was this sort of epiphany moment. He just took everyday things we had and did something really cool with them." He spent the next 20 years gradually collecting similar projects before he took the plunge and wrote a book about them. Many of his creations are already out there, at least in principle, though he says he will always devise a version that works and can be made without machine tools. Publishers kept turning him down (for safety reasons, he suspects) but then a like-minded agent in New York took him on and landed a deal.

When I suggest his books plough a similar politically incorrect furrow to the immensely popular Dangerous Book For Boys, albeit for rather older boys, he recoils a little. "There's quaint stuff from the Twenties and it's great for getting your kids away from the TV, but that book isn't remotely dangerous."

His latest book ratchets up his own danger factor "a notch", he says. Still, there are some things even he considers too risky to mention. Thermite is one – "easy to knock out and reportedly pretty cool but it can burn through soil and is used for welding railway tracks". Does he have any golden rules? Never mess with flaming liquids, he says, but cannot think of any more. "I don't really have rules. Except perhaps that virtually nothing can't be blown up." Seconds later, a large mushroom cloud rises over his garden as the home-made gunpowder works its magic on a leading brand of non-dairy coffee creamer.